The Guild of Turners

The Company is the successor of the Guild of Turners whose exact origins are unknown. Unlike the products of the potter, wooden objects are perishable, so the earliest date of turning is not known exactly. However, turned wooden bowls excavated from peat bogs at prehistoric levels show that the craft is certainly many thousands of years old.

In the Pipe Roll of 1179-80, there is an isolated reference to “the Guild of Strangers of which Warner le Turner is elderman”. Interesting though this is, it cannot be regarded as evidence of the existence of a Guild of Turners. In 1310, however, turners were in a position of some authority in their own craft: “Henry the turner, dwelling in Wood Street, Richard the turner, John the turner in St. Swithin’s Lane, Robert the turner, dwelling at Fleet, William the turner, without the gate of Bishopsgate and Richard le Corveiser, dwelling in Wood Street” were sworn before the Mayor and Aldermen not to make any other measures than gallons, “potells” (two quarts) and quarts, to make no false measures such as “chopyns” (about a pint) and “gylles” (half a pint), and to bring to Guildhall any false measures wherever found.

In those days, drinking vessels and measures for holding liquids, as well as dry measures for goods such as corn, were mostly made of wood and were essentially the work of the turner. Fifteen years earlier, a similar ruling by the Court of Aldermen regarding the making and checking of measures had made no mention of the Turners. Perhaps, therefore, the first beginnings of the Guild of Turners can be assigned to a date between 1295 and 1310.

Early Days: Growing Importance

In 1347, there is evidence that the Guild was growing in importance. Turners were summoned before the Mayor and Aldermen and instructed that their measures must conform with the standard of the Alderman of the Ward in which they were used. Each turner was to have a mark of his own, to be placed on the bottom of his measures when they had been examined and found to reach the standard. He was also to register his mark in Guildhall. Further, the turners of the City were given a virtual monopoly of the sale of measures, which undoubtedly advanced the position of the Guild in London where, throughout the Middle Ages, most of the trade of the country was carried on. Wood Street was for centuries the centre of turning in the City.

The products of the turner’s craft were wooden measures and a great variety of small objects used in the home, on the farm and in industry. The turner has always played an important part in furniture-making, providing table and chair legs, rails, chair spindles and much embellishment. For centuries, he has turned the balusters of staircases, landings, and balconies for buildings and for the poops and sterns of’ sailing ships, as well as pulleys and many other wooden components used on sailing vessels.

By 1435, the Guild of Turners was firmly established. In that year, John White and John Hendon, described as “Wardens of the craft of Turners” laid a complaint before the Court of Aldermen that “foreigners” were making and selling within the City certain measures which were false and deceitful, and asked that the Wardens be granted “the search and oversight” of all such measures brought into the City before being put on sale. The petition was granted and officials of the Guild were authorised to examine all wooden measures which were to be offered for sale in the City. The minutes of later Court meetings show that this right of search and oversight of turned goods in the City was exercised for at least 300 years – well into the 18th century.

In 1479, the Mayor and Aldermen approved a full set of ordinances submitted by the Turners. They are typical of the regulations of a craft guild of the period whose purposes, besides supervision and protection of the members’ trade, were brotherhood, mutual help, charity and religious observance.

Hall and Royal Charter

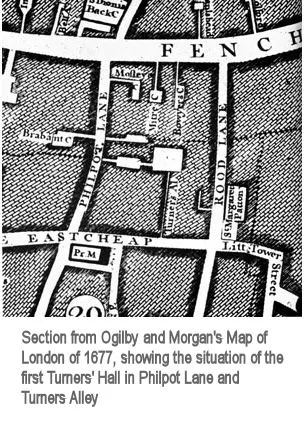

The close of the 16th century saw three notable developments in the Turners’ history. First, in about 1590, the governing body of the Guild decided that the dignity of a Common Hall was both desirable and justified. A substantial mansion in Philpot Lane, off Eastcheap, was leased in 1591 and occupied as the first Turners’ Hall for a period of 146 years, broken only by rebuilding.

Second, with the year 1593 the Guild’s own records begin and continue until the present time; and third, in 1604 King James I granted the Turners their first Royal Charter. This is still in the Company’s possession, as is their second Charter granted by James II in 1685.

The Turners made good use of their Hall for their own business and social activities. It was freely made available to other Livery Companies and was also let out for other purposes such as preaching, dancing, weddings and funerals.

Sadly, this was brought to an end by the bursting of the South Sea Bubble which, in 1726, bankrupted first the landlord of the Hall and then the legal representative of his estate. After expensive legal proceedings stretching over ten years, with no successful end in sight, the Company reluctantly decided to abandon the Philpot Lane Hall. So the second and last Turners’ Hall, a merchant’s house in College Hill, off Cannon Street, was purchased in 1736.

Decline

The new Hall was in fact never used by the Company for its dinners or other big functions, as its “Great Room” was no more than a large Court Room. In 1756 it was let and, in 1766, finally sold.

Within a few years of occupying the new Hall, the Company’s financial situation had become straitened. There may well be a connection between the Company’s declining fortunes at this time and the changes in English furniture styles. The early walnut period (1660-90) was the heyday of furniture turners, but every style of the 18th century, from Queen Anne onwards, was against them, and they suffered financially.

At the same time the Livery Companies generally were tending to decline as an economic and political force. This was an inevitable result of the expansion of trade and the influx of population, which finally burst the bonds with which the medieval craft guilds had sought to control their respective trades. Another reason was the change in the complexion of the Companies’ membership. Even though employers still constituted the Livery, the proportion of actual artificers among them decreased, and these became outnumbered by journeymen and other manual workers in the craft.

The affairs of the Turners’ Company show a continuing decline throughout the second half of the 18th and the first half of the 19th century. Freemen became more and more unwilling to join the Livery. Lack of interest spread through the Livery to the Court itself’, with Assistants electing to pay a fine to be excused from the office of Warden and even that of Master. Through obsolescence and artificiality, the Company was almost dying on its feet.