A Past Master of the Turners’ Company, Professor James Tennant, Mineralogist to Queen Victoria, supervised the recutting of the legendary Koh-i-Noor diamond. He transformed it from a large, flawed gem to the fabulous 105.6 carat oval brilliant to be seen in the Queen Mother’s Crown today.

The recent funeral of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II brought into public view the Imperial State Crown, worn by the Queen at her Coronation, then every year at the State Opening of Parliament and finally placed on her coffin for her State Funeral. But there is another magnificent crown in the Crown Jewels named the Queen Mother’s Crown. It was last worn by Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother and displayed on her coffin at her State Funeral in 2002. It has been said that it was the late Queen’s wish that this crown should be worn by Camilla the Queen Consort at the Coronation of King Charles III in May 2023 although this has now been cast into some doubt. A number of people, and indeed the Indian Government, have indicated that there may be an insensitivity in parading a crown featuring a diamond originating from a larger gem which some believe could be seen as a symbol of 19th century colonial plunder.

The centre piece of the Queen Mother’s Crown is the incredible Koh-i-Noor diamond, still one of the largest cut diamonds in the world. It was originally discovered in India but changed hands many times between various factions in Asia and the Middle East before being “gifted” to Queen Victoria in 1849 as part of the Treaty of Lahore. Originally the stone was of a similar cut to other Mogul Empire diamonds now in the Iranian Crown Jewels but it was seen as lacking sparkle when displayed at the Great Exhibition of 1851 and so Prince Albert asked for it to be recut into the “oval brilliant” we see today.

For technical advice on the cutting Prince Albert turned to James Tennant, first Professor of Mineralogy at newly founded King’s College, London, and the Queen’s Mineralogist since 1840. Prince Albert ordered that the task should be organised through Royal Jewellers Garrard & Co but the cutting undertaken by Mozes Coster, well known Dutch diamond merchants.

With the first cut made ceremonially by National Hero the Duke of Wellington, and under the guidance of Professor Tennant, flaws were cut away and, from its original 186 carats, a dazzling stone of 105.6 carats was created. It was mounted in a honeysuckle brooch and a circlet and thereafter belonged to Queen Victoria personally.

On Queen Victoria’s death the Koh-i-Noor was re-set into the Crown of Queen Alexandra, wife of Edward VII and became part of the Crown Jewels, ultimately becoming part of Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother’s Crown in 1937.

James Tennant – Mineralogist to the Queen

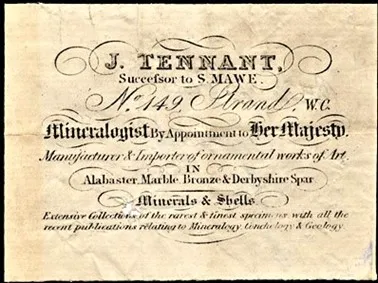

Born in 1808 James Tennant came to London from Nottinghamshire. He studied Geology and Mineralogy, with Chemistry under Sir Michael Faraday at the Royal Institution, and worked with mineralogy dealer John Mawe at 149 The Strand in London. After Mawe’s death in 1829, Tennant managed the business with Mawe’s widow, Sarah Mawe, and eventually acquired her shares and became Mineralogist to Her Majesty Queen Victoria in 1840.

James Tennant attended the parish church of St Mary-le-Strand London, not far from his business premises at No 149 the Strand and there met Watchmaker John Jones a longstanding Liveryman of the Turners’ Company and based at No 336 the Strand. John Jones was twice Master of the Company, in 1852 and 1861, initially at a time when the fortunes of the Company were at a low ebb. The tide was turned when in 1864 it was decided that any member of the Court could propose anyone for admission to the Freedom and Livery without payment of fees within a period of 6 months. Eventually by 1870 an altogether healthier and more robust atmosphere became apparent in the Turners’ Company with no shortage of eminently suitable people seeking and gaining admission to the Livery.

Knowing Past Master John Jones, a Churchwarden of St Mary-le-Strand, and famous for his position as the Queen’s Mineralogist, James Tennant gained his Freedom by Redemption in the Turners Company in September 1869. He quickly went on to become Renter Warden eighteen months later in May 1871, then Upper Warden in May 1872 and Master in May 1873.

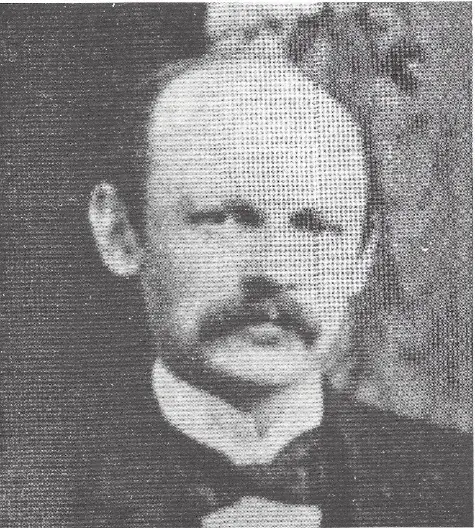

Professor James Tennant FGS, Master of the Turners’ Company 1873 – 1874

This fine portrait of Professor Tennant is in the Vestry of the Church of St Mary-le-Strand presented in recognition of his work for the Church and its local schools. It was commissioned by Baroness Burdett-Coutts and said to have been executed by a painter by the name of Rogers.

In 1854 the Turners’ Company introduced a competition for the best specimen of turnery executed by an apprentice of a member of the company. The competition had modest beginnings but was subsequently opened up to all turners and eventually attracted so much support that it became held at the Mansion House with the generous permission of the Lord Mayor for the time being who usually presented the prizes.

Turning Prizes in Semi-precious Stone

In 1873 prizes were awarded for the first time for turning in stone such as agate, alabaster, fluorspar, granite, jasper, jet, marble, porphyry and serpentine. The next year lapidary work was chosen covering ruby, sapphire, emerald and spinel, topaz, seal stones and diamonds. Baroness Burdett-Coutts, an enthusiastic collector of mineral specimens, had been admitted to the Honorary Freedom of the Company in 1872 and provided generous sums for the cash prizes. Professor Tennant, then the immediate Past Master acted as judge for the minerals; Honorary Liveryman Sir Gilbert Scott, Victorian Gothic Architect and designer of the Albert Memorial, was appointed to judge work executed in stone.

James Tennant retired from his post as Professor of Geology at King’s College in 1869 but retained his post in Mineralogy and went on to become Curator of Baroness Burdett-Coutts collection of minerals. He maintained a life-long interest in diamonds and is widely credited with predicting the probability of finding diamonds in South Africa based on similarities with the geology of Brazil.

James Tennant never married. He died in London in 1881 aged 73 and a wealthy man; his will was executed by his long-time friend at St Mary-le-Strand and fellow Past Master of the Turners’ Company, John Jones. At one time James Tennant was reported in the Illustrated London News as owning a delicate yellow diamond from the Cape, cut into a brilliant and weighing 66 carats – exceeding in brilliance any diamond in the British Crown.

There is also a portrait of James Tennant as Master Turner in the art collection of King’s College London, attributed to the artist Joseph Sydney Willis Hodges (1828 – 1900).

Written by Colonel John Bridgeman CBE TD DL

Past Master (2014/15)